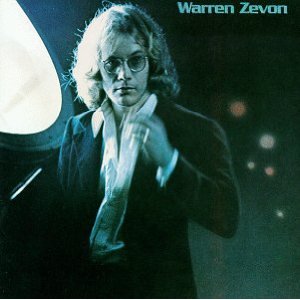

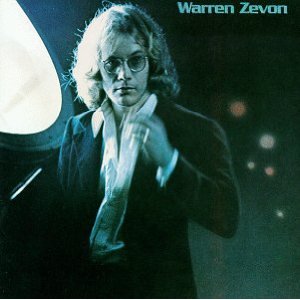

The album cover:

A photo of the 29-year old Warren Zevon in black suit and unbuttoned white shirt, a dim, noirish image with only an offset stage light providing illumination.The image indicates a bit of Zevon’s past (he was a band leader for the Everly Brothers before starting his solo career) and future (he was friends with David Letterman and often filled in as band leader for Paul Shaffer on Letterman’s show).

Warren Zevon, recorded in 1975 and released in 1976, was Zevon’s major label debut. He had spent much of the early ’70s trying to get a record deal, without success, and had actually moved to Spain for a period, where he had a regular gig in a bar owned by a former mercenary (the inspiration for the song Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner). Jackson Browne talked him into returning to Los Angeles to record this album, which Browne produced. Zevon was a true songwriter’s songwriter, with both the good and bad implications of that title: He never achieved the commercial success his talent seemingly deserved (at least in part because of his self-destructive alcoholism and drug habits), but he was universally respected by other musicians. Just look at the list of contributors on this album: Jackson Browne, Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, Don Henley, Glenn Frey … it’s like a ’70s Southern California Hall of Fame.

The first sound you hear:

The opening solo piano riff of Frank and Jesse James. Zevon grew up mostly in Fresno, California; he’s been quoted as saying, “I’m the smartest guy to ever come out of Fresno,” but he did spend time as a youth in Fresno taking lessons from Igor Stravinsky, and his classical training shows in the intricate piano work throughout the album.

The last sound you hear:

The long fade out of a beautiful string arrangement in the coda of Desperados Under the Eaves. Much more on this song below.

Track by Track:

The album opens with Frank and Jesse James, a narrative song that tells the story of the famed outlaws in a sympathetic voice (“No one knows just where they came to be misunderstood/But the poor Missouri farmers know that Frank and Jesse do the best they could.”) Zevon was one of the smartest songwriters ever, and his work tended toward stories, showing the influence of both folk music and the westerns and detective novels he loved. His lyrics evoke the landscape of the West: “Keep on riding riding riding/Cross the rivers and the range/Keep on riding riding riding/Frank and Jesse James.” The jumping, syncopated piano work evokes those mountain ranges as well.

A chunky electric guitar leads us into Mama Couldn’t Be Persuaded. Zevon wrote many of the songs on this album while living in Spain and looking back over his life and seemingly failed career. As such, many of the songs are autobiographical: The chorus of this song is straight from Zevon’s parents (his father was a professional gambler): “My mama couldn’t be persuaded when her daddy said/Daughter don’t marry that gambling man.” He explicitly reveals it’s his family’s story in the verse when he sings “They all went to pieces when the bad luck hit/Stuck in the middle, I was the kid.”

Next is the upbeat acoustic Backs Turned Looking Down the Path, which features Lindsey Buckingham playing lead guitar and Jackson Browne on slide. The song shows folk and country influences, and the best part is the chorus: “People always ask me why?/What’s the matter with me?/Nothing matters when I’m with my ba-aby/With my back turned/Looking down the path.”

The fourth track is Hasten Down the Wind, a mournful breakup song with this lovely chorus: “She’s so many women/He can’t find the one who was his friend/So he’s hanging on to half a heart/He can’t have the restless part/So he tells her to hasten down the wind.” Linda Ronstadt covered this and used it as the title track for her Grammy Award-winning album.

The next track is titled Poor Poor Pitiful Me, but it’s anything but mournful. Zevon had a great sense of humor, and it’s never more on display than in this tongue-in-cheek appraisal of the L.A. hookup scene. The chorus goes “Poor, poor, pitiful me/These young girls won’t let me be/Lord have mercy on me/Woe is me.” He tells stories about a couple of encounters, the first of which goes: “I met a girl in West Hollywood/I ain’t naming names/She really worked me over good/She was just like Jesse James/She really worked me over good/She was a credit to her gender/She put me through some changes, Lord/Sort of like a Waring blender”; the second features one of the funniest moments ever recorded in song: Zevon sings “I met a girl at the Rainbow bar/She asked me if I’d beat her/She took me back to the Hyatt House…” and then he stops for a moment before muttering, “I don’t want to talk about it.” Set to an upbeat barroom piano riff and stellar electric guitar licks, it’s an oxymoronic song that’s a Zevon classic.

The French Inhaler is, on the surface, a song about a failed-actress turned prostitute and an alcoholic in a Hollywood bar who falls for her. It’s actually another autobiographical song, a “fuck you” to Zevon’s first wife, which ends with an audible blown kiss.

The next track is the gorgeous Mohammed’s Radio, which layers piano, electric guitar, and saxophone, along with harmony lyrics from Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks. It’s a song about weighing the struggles of the day-to-day with spiritual crisis: “Everybody’s working/Trying to make ends meet/Still can’t pay the price of gasoline” in the verse, while the chorus soars: “Don’t it make you want to rock and roll/All night long/Mohammed’s Radio/I heard somebody singing sweet and soulful/On the radio/Mohammed’s Radio.”

Zevon switches to a heavy thumping bass track on the next song, the anthemic I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead. The title says it all. Zevon wrote about death so often, and in such a brash, fearless manner, that he nicknamed himself a “travel agent for death.” Sadly, this became a self-fulfilling prophecy, as Zevon died of cancer in 2003 at the edge of 56 (though his death was actually less attributable to his drinking and smoking habits than to years of being exposed to asbestos while sleeping in an attic as a kid). Even shortly before his death, Zevon’s final words of advice to David Letterman were pragmatic: “Enjoy every sandwich.”

We go back to the light acoustic milieu for the classic Carmelita. The song starts, “I hear mariachi static on the radio,” and the guitars (rhythm played by Glenn Frey and lead by David Lindley) show a distinct mariachi influence. It’s a song about being down and out in East L.A., with a chorus that goes: “Carmelita, hold me tighter/I think I’m sinking down/And I’m all strung out on heroin/On the outskirts of town.” My favorite part, though, is the final verse, about a writer selling his typewriter so he can head down to a notoriously seedy LA. street to score: “I pawned my Smith Corona/And I went to meet my man/He hangs out down on Alvarado Street/By the Pioneer Chicken stand.” Is it weird that I think this is the most romantic song ever?

Join Me in L.A. carries every bit of the darkness of a Raymond Chandler novel, as he urges listeners to join him on the dark and seedy streets of Los Angeles. The backup vocals are provided by Bonnie Raitt and Stevie Nicks.

The album closes with one of my favorite songs of all time, Desperados Under the Eaves. It’s another down-and-out in L.A. song that begins: “I was sitting in the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel/I was staring in my empty coffee cup/I was thinking that the gypsy wasn’t lying/All the salty margaritas in Los Angeles/I’m gonna drink them up/And if California slides into the ocean/Like the mystics and statistics say it will/I predict this motel will be standing/Until I pay my bill.” The song contains all of Zevon’s trademarks: the piano work, the darkness, the sense of humor–and then it takes it up a notch. The final verse goes, “I was sitting in the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel/I was listening to the air conditioner hum/It went…” at which point Zevon begins to hum the song’s melody. He is soon joined by backup singers and then a string arrangement, all of it coming together in a beautiful harmony, and then Zevon takes a lead vocal, singing over that harmony, “Look away, down Gower Avenue/Look away.” It’s a lament, a broken man looking for some way out and unable to find it, but it’s a lament so powerful that it sends the soul soaring, a coda to not just the song, but the album as a whole. If those two minutes of music doesn’t move you, then I’m sorry, you just don’t like music.

The signature track:

It’s so hard to choose. Do you go with I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead, a song that’s tragically so definitive for Zevon? Or the beloved Carmelita? Neither of those would be bad choices, but for me, the album closer, Desperados Under the Eaves, for the reasons outlined above, will always be the song that defines this record.

The signature lyric:

“I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead” would be a worthy choice. But, again, I have to go with that lyric from Desperados Under the Eaves: “And if California slides into the ocean/Like the mystics and statistics say it will/I predict this motel will be standing/Until I pay my bill.”

The essence of the album:

As I said earlier, Warren Zevon is the least famous artist on my Desert Island Albums list. However, he may be the most important. My love of music starts with Zevon. My father is a huge Zevon fan, and one of my earliest memories is riding in a car with him to my uncle’s cabin in the Catskills, with Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner (from the 1978 album Excitable Boy) playing on the stereo. The first album I ever owned (On cassette! I’m old!) was Zevon’s Greatest Hits. My uncle and I often sing Carmelita together at our Friday night jam. Zevon’s music is like a Goldman family heirloom.

My uncle (on the right) and I (in the middle) at our Friday night jam

To go even further, I identify quite a bit with Zevon: I feel like I’m a pretty talented person who hasn’t had as much career success as I’d like, and while that’s definitely not all my fault, I have to admit that at least a little bit of it is because of my sometimes self-destructive behavior. When Zevon sings about everything around him being destroyed by a natural disaster, and yet somehow his motel surviving long enough to insist that he pay his bill, I know exactly how he feels.

One last note: Zevon was diagnosed with terminal cancer about a year before his death, and he recorded a final album, My Ride’s Here, as his health deteriorated. Keep Me In Your Heart For A While is the closing track on that album, and I defy you to keep your eyes dry while you listen to it.

Find all my Desert Island Albums here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.